W.C. Clark: Soulin’ the Blues By Josep Pedro

Known as the Godfather of Austin’s blues, W.C. Clark is one of true masters of Austin’s music scene. Clark, who has been playing for over 40 years, grew up in East Austin and soaked in the blues at places like the Victory Grill and Charlie’s Playhouse. An inspiring guitarist, groovy bassist and an incredibly moving vocalist, Clark is one of the successful local musicians that boosted Austin’s worldwide music expansion during the ‘60s and ‘70s.

Growing up in a music family, W.C. Clark started off his brilliant career around Austin Black music legends like T.D. Bell, Erbie Bowser and Grey Ghost, and helped to break racial barriers in town along with Blues Boy Hubbard. Clark then toured with soul man Joe Tex enjoying the chance to play with people like James Brown, and returned to Austin to make a name of his own while mentoring talented young musicians such as Angela Strehli, Marcia Ball, Jimmie Vaughan, and Stevie Ray Vaughan, for whom he co-wrote “Cold Shot”.

One of most prolific bluesmen in Austin, Clark’s stunning, positive-vibe compositions can be found in his extensive discography, as well as in his regular live shows. Powerfully versatile in his effectively subtle blend of blues, soul, and R&B, W.C. Clark has created his own sound and musical language while keeping a firm bond with tradition. I met W.C. Clark at the Historic Victory Grill, the place where he got started and still feels linked to.

Growing up with music

Music in Austin

Style

Blues for Tomorrow

Growing Up With Music

“When I came up and started playing, I didn’t really have to study real much. All I had to do was just bring the stuff out through my fingers that I already knew that I could feel from the experience.”

What was your first instrument?

My first instrument was guitar. I was raised up in a gospel neighborhood, and there were a few guitar players around Austin and St. John, where I was raised at. They will be playing the blues and I was learning to play the blues on the guitar first. There used to be a country & western club over on North Lamar called the Starlight Club. I would go over there, 13 or 14 years old, and sit around on the porch and start playing the guitar. After a while, somebody will come through the door and said: “Come on in!” [That was] back in the heavy prejudice days, and the next thing I know I’m inside playing and people is throwing money on the floor. I’d go home with $35 or $40, 14 or 15 years old, and that was pretty good.

Bass came along after because I spoke to my cousin, Big Pete Pearson. He was a bass player so I started hanging around with him and learning bass. When I came over to Victory Grill the first thing I was playing was bass. But I had already learnt a lot of country & western and gospel guitar playing. I played bass for quite a while and then I started playing guitar again and formed a band of my own. Next thing I know I was playing bass with Stevie Ray Vaughan and Triple Threat. That was before Double Trouble. So, right now people tell me: “I heard you play bass” and I’d say “bass is my real instrument, I’m still learning guitar.” That’s true. I don’t if you could ever finish learning music. The way it’s designed, I don’t think there’s a limit.

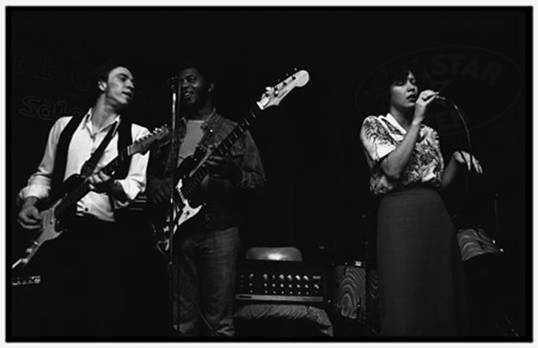

Triple Threat Revue (Stevie Ray Vaughan, W.C. Clark and Lou Ann Barton)

Do you also like jazz guitar?

Yes, oh yes! I go back to Kenny Burrell and Wes Montgomery coming up to George Benson. Just about every kind of music it’s good, I’m interested. So I’ll play country music, a little jazz, blues, soul, rock. The main thing is giving the crowd excitement. I’m gonna work on it and I’m gonna get the crowd excited, and then I can go home and rest ‘cause I did a good job.

What was the importance of the black church in the development of Black music?

As far as the music, in the music scene of the old days the blues wasn’t so welcome. My grandmother used to say: “you still out there playing that music? Messing around with that painted girls? Painted girls ain’t for nothing but a show.” She was a half Cherokee Indian and she had a lot of power to the family.

She was kind of like the mother of the local church. Me as a young boy, my job was to walk her to church and walk her back home. So I was around that and heard all the singing, all the gospel quartet singing. When I came up and started playing, I didn’t really have to study real much. All I had to do was just bring the stuff out through my fingers that I already knew that I could feel from the experience. For instance, when your mother and your grandmother is washing, cooking, whatever, this is what they’re doing: [WC Clark starts humming a tune]. You don’t have to have a song. You just find one note and then you go up and under. And you hear that, that’s a haunting sound. I used to go around the house because I was supposed to be doing something else but that sound’s got me.

So, when I did my first Austin City Limits I had taken my mother with me up there and she was really excited. On the way back home she said: “Well son, this is not the type of music we programmed you to play but I just wanted to know I’m very proud of.” What she meant was that when they’ll be humming that sound around me, they knew what they were doing then. They knew I was listening. I thought I was discrete but I wasn’t! They knew it so they just kept pouring it on me. And working in fields, the same thing. So, like I say, as far as the intervals of the scale, the harmony… they were all in me. I just had to develop.

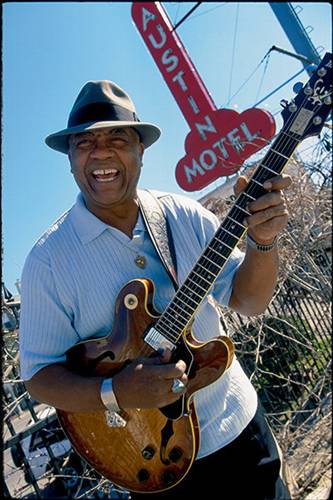

W.C. Clark (photo Clay Shorkey)

I do a lot of teaching. In fact, my younger student is 8 years old and his little hands are so small that I have to teach him one side of the guitar at a time. The way I do it is I get on my computer and I play all the parts except the drum machine. I play the bass, the rhythm, the lead, the piano parts and the singing, and sometimes I put back-up vocals. Then I explain it, the whole thing: keys, scale, notes… and I put it all together on a CD. I go to the student and I sit down with him that one time and go completely over it with him. He’s got his recorder, his got the CD with all the instruction and I’ll see him again in about two weeks and when he comes by he’ll know it. It’s a lot easier that way because when it’s one-on-one they feel like “you’ve been playing all these years and that’s what you can do it, and I’m just getting started so I can’t do it.” The way I do it with the CD, childs won’t feel that and they will learn faster.

I got Mr. James Polk right up there who I’ll thank for a lot of my learning. Right up there [WC Clark points at the James Polk biographic board hanging in the wall]. He was teaching at Southwest University at San Marcos. I will play bass with him and sometimes and they will put sheet music in front of me but I couldn’t read music. I didn’t need to. I will do jazz shows playing bass. I could still hear the passing tones. If a person is playing correctly, he’s gonna put out a passing note for you to hear. That’s what I could play with those guys without reading music. So I got James Polk to thank from a lot of my music knowledge.

Music in Austin

“It was always something going on. Gatemouth will come through here and the band here will play with him, and Johnny Copeland; all the blues artists coming out of Houston during that time.”

W.C. Clark (standing at left post) at the Victory Grill, circa 1955, T.D. Bell on guitar, Datney White on piano, and George Alexander on drums. (Photo courtesy Tary Owens and T.D. Bell)

What does Victory Grill mean to you?

I have to start back when I was 12 or 13 years old. I had been raised up in a gospel neighborhood from the old style. I couldn’t listen to very much blues in my house. So what I did, follow the guys that was playing around my area. They would play the blues and I will be there. You know that old saying, “it takes a neighborhood to raise a child”? Well, it was like that. I will be there for a while till it was time to go home and they will take me. I got exposed to the blues like that.

I had a cousin, we called him L.P. Pearson. They also called him Big Pete Pearson and he’s like an icon of Phoenix, Arizona blues. Anyway, he was already playing over here in town, in the Victory so I would sneak over to see him at 15 or 16 years old. People outta here knew me so they protected me and stuff. I would have a shine box to get by and I was able to come in and listen to him play. Then I started sitting in on the bass. Before long, Bit Pete did something else and I started playing with T.D. Bell, who was the guitar player. They called us T.D. Bell and the Cadillacs.

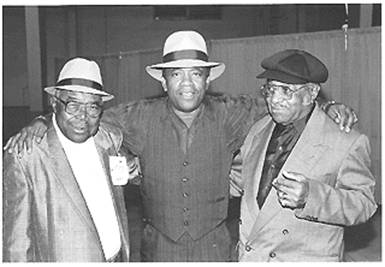

W.C. Clark with Erbie Bowser (left) and T.D. Bell (right) (photo John Carrico)

The scene at the Victory Grill was always crowded, always. They had wonderful blue Mondays, and singing contests. In fact, Bobby Blue Bland was stationed in Fort Hood for a time and he would come through here on Monday nights to the talent show and win it. Next thing I know he was at a record label. It was always something going on. [Clarence Brown] Gatemouth will come through here and the band here will play with him, and Johnny Copeland; all the blues artists coming out of Houston during that time. There was a record label there called Peacock with Don Robey, and they were all coming down through here.

Across the street there was the (…) Lounge, a small place, and bands will play there and bands will play here. Next door building used to be I.L club; V&V first, then I.L. Club, then Charlie’s Playhouse. They kept the street really crowded, mostly on weekends but Monday nights too. And when they got special events, that was advertised and a big group would be here. During the time, the blues scene extended down to 6th Street but it was just so far up 6th Street you could go. When you passed Red River on 6th Street, then business’s started getting real prejudiced and skeptical. You couldn’t have any blues beyond that point. It was stretching over [the west] side but it was all coming from here, [East] 11th Street. This club [the Victory Grill] used to be owned by a lady called Big Mary. Big Mary was big and she was a home bouncer. She picked me up a couple of times in the alley and brought me out. Then Johnny Holmes and the lady who’s here now, Eva [Lindsey].

Actually, the building was here before I even came on the streets and I am 70 years old now so that will let you know more or less how long it has this been here. As far as the Victory Grill is concerned, I remember it was closed for a long time and the band started getting together doing benefits along with the city, opened it back up again and turned it into a historical mob. Not turn it because it was already that, they recognized it. Harold McMillan has done a lot for the Victory Grill, booking bands and doing work with the city and stuff.

I think Ruth Brown played here one time. Lightnin’ Hopkins played here. A lot of those old guys they played here, and a lot of guys who came from San Antonio and Dallas. People like Spot Barnett will come here and play, and we will go to San Antonio and play. One thing about the Victory, back then there was an army base in Bastrop. It was called Camp Shrief I believe. The soldiers in Fort Hood and Bastrop will come to 11th Street and that also kept the clubs crowded with people moving around.

Of course, the Victory Grill was part of the “chitlin’ circuit”.

Chitlins was a well known ghetto food, I’d say. I’ve eaten a lot but there’s a lot of stuff you have to do to it. You have to clean it and get all the fat off. Actually it’s the intestines. Just about every club will be broad in chitlins. See, now you go in a store and it’s gonna cost you some money to take that. But back then, all you had to do was go to the lavatory and get it free because they didn’t sale oxtails, chitlin’s and tripes. They just give it away. But then somebody see how people eaten them and it started growing bigger and bigger so they started selling it. That’s what the chitlin’ circuit was and there was chitlins here, chitlins there, chitlins in every club.

Talk to me about Antone’s.

Well, I mentioned earlier that it was so far up to 6th Street you could go with blues music during the time. Clifford Antone was in some kind of way able to break that code. He went passed Red River all the way up by the Driskhill hotel. That was really taboo then because the Driskhill hotel was the classic hotel in town. He was able to do that. He opened up a club and started having blues right there. He was bringing in all of those guys who used to play here [Victory Grill] and in Charlie’s Playhouse: Pinetop, Gatemouth, Freddie King… I don’t think B.B. ever played in Antone’s, I don’t know why but I don’t think he ever did. Anyway, all of those guys so there was a blues scene gathering right there in 6th Street. As you know, it went from 6th Street to Anderson Lane and then it came to Guadalupe, and then it went to 5th Street where it is now. That was the blues scene and he was always doing good to musicians and he brought in all the Chicago talent. It was always good.

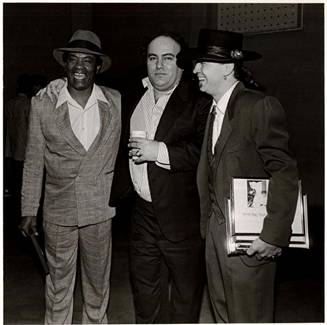

W.C. Clark, Clifford Antone and Stevie Ray Vaughan

After being in the Austin live music scene for so many years, what do you think have been the most important changes?

Well, the change is like this: the Victory Grill and Charlie’s Playhouse, and some university students. There was a few whites who will come into the east side and listen to the blues. Some musicians like Stevie did that. He came along later though. But Bill Campbell, he used to come over here. The point I’m getting to is the university students will leave and come over to the Victory Grill and Charlie’s Playhouse, and that was the beginning of the change of the movement in Austin. There were still coming to the East Side Lounge from the University of Texas, and fraternity’s parties. But when they started coming over here to Charlie’s Playhouse and the Victory Grill the whole scene changed. That’s when the west side, the south side, and all of Austin started filling up with the blues and the white started playing the blues.

That was a change there because all of the sudden you could make more money playing the blues than you used to. There was more places to play, the union was getting more thankful and the chamber of commerce and the city council was recognizing the movement. Musicians started doing tourist commercials; I did quite a few tourist commercials, and commercials for the air flights. I guess it’s still at the airport, I got a lot of my stuff in a display like that for my accomplishments and things, and so it’s at the airport so the tourists can see. That was bringing the people in here ‘cause we got a lot of jobs. I’ll go up there once in a while and play for the people coming in and that helps the city. Now other musicians are doing the same thing. So when they go out that night or a few nights after they will go and see a band they like.

As far as the blues itself, there has been a little change. Different categories have gotten out: gospel blues, rock blues, rhythm and blues… it was all one back then. There was no need to label it because it was just the blues. Texas had a more of a backbeat on the drums than Chicago. Chicago blues shuffles were more of a loose shuffle than Texas that was straight, more like swing [W.C. Clark shows the beat] and Chicago shuffle was more like [W.C. shows the beat again]. That was the difference. When they say the Texas shuffle they’re speaking of a strong backbeat. And B.B. King will agree with me ‘cause he talked about it a lot too.

W.C. Clark with his cousin Big Pete Pearson (photo Bob Corritore)

There was a lot of things going on in communication before multiple tracks came along. The bass player had a job and the drummer during the time they will just say he was a time people. Each instrument in the band if they are doing the right job they can keep it there and make it lock in, what a musician will call “in the pocket”. If you got a shuffle, then the bass player gives the rudiments to the drummer. If the bass player will hear there’s a hole that need to be filled in, then he would be doing [W.C. sings the bass line]. That’s kind of lost. Drummer and bass players fight each other these days. Every time somebody said: “pick it up, pick it up!” well, that’s the bass player’s jobs to do that. The drummer will pick it up and start introducing stuff before it happen; bass player will give him a signal.

Everything is designed for the soloist or the singer. Nobody is supposed to overplay. Everything is supposed to be in the background, in the rhythm section volume. That’s kind of lost a little bit because for bands it’s kind of hard to volume everything like they needed ‘cause of huge, gigantic PA systems. There’s somebody you can’t hear enough, there’s somebody you hear too much, and sometimes that can cause a lot of arguments. Just like I say though, there’s gotta be a pocket and in that pocket is where it’s gonna move on back to the two tracks.

When you had two tracks you couldn’t waste all that money recording over, over and over. Back then you might see on some of the old albums someone says: “you did it all in one take”. That was a great thing to do because you had the two tracks and you did it all the first time. Well that’s because the bands will be doing the things I am explaining and they wouldn’t rehearse at the studio. Another thing where a lot of musicians get mixed up today is there’s a difference between practicing and rehearsal. You practice at home, but a lot of the musicians come to the rehearsal to practice. “You don’t know it? You’re supposed to know it before coming here!” [Laughs] Well, that’s a little problem too now.

Those are the changes but the blues is still being delivered. It dies down and another generation brings it back up. I see a lot of young players all over the United States. With 12 or 13 years old playing the blues. Kids playing the blues, you know. I think to myself: “how can they have the blues? Why did I have to practice all these years to learn it?” They already know it and are already playing it. Some of them are on the stage; the Peterson Brothers, 13 or 14 years old, playing the blues, real blues.

That generation is coming along. It always goes up, down and come back up. It’s a little bit lost out of the original but as long as it’s going on, it keeps moving… Everything in time changed and so is this it. As long as the feeling is there, it’s ok. That’s why I’m still doing it.

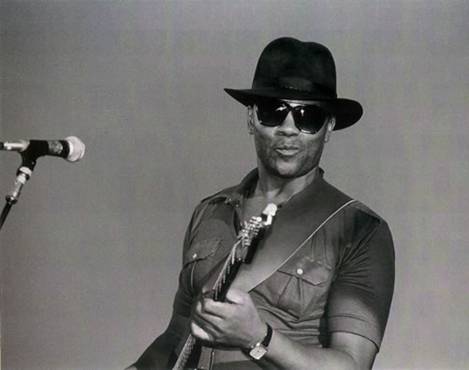

W.C. Clark (photo Scott Newton)

Austin has been named the Live Music Capital of the world. What do you think about that?

I think we are working real hard trying to keep it up at that level but I’m not sure there’s more music going on in Austin that it is anywhere else now. ‘Cause I’ve played in a lot of different places, in Canada and other countries and the blues scene is pretty large. But Austin has got the Music Capital name over the world because I’m known as the Godfather of the Austin scene, then Stevie Ray Vaughan, Jimmie Vaughan, and other musicians that made Austin famous from record labels. When they named it that, there was a music scene every night just about everywhere… at least 12 or 13 clubs through the week were putting on good music. It’s a little bit slower now.

Another thing is, I’ve seen this happen a couple of times before, we are right at the end and beginning of the generation gap and when that happens in the scene, a lot of the blues musicians get older and they are not local anymore. They are in the fields trying to make money and in other states. That’s leaving the oncoming musicians around Austin that are playing local, to hold that name.

When that happens, you get more rock and more reggae than jazz and blues. We still got the music here, the music is still going on –and country music is still going on- but I think that back then there were more active clubs that had live music than there are today. Clubs are still here but I don’t think the scene is as good as it was. Like I say, the generation gap has got a lot do to with it because some of the club owners have got to the age when they don’t wanna run clubs anymore or when some of their kids inherit the clubs they were not interested in going the traditional way and they would change it. Not only here, in other places too but still the Live Music Capital of the World.

What are the differences between an artist who stays local and someone who manages to get beyond that point?

For one thing, mentor’s. As long as the blues scene mentor’s was local for the young artists, oncoming musicians, the traditional factor will remain as much as possible but when the older musicians; myself, Jimmie Vaughan, Stevie, Angela Strehli started going out in the field, there were no many more blues mentor’s left local for the young blues guys to listen to and learn from so that was probably the change in the sound.

When we would come back to Austin to play, we will always have crowd but the thing is the audience that was supporting the music scene then was more or less the age of the musicians and as the musicians grew older, so did the audience. That was part of the generation gap that went older and wasn’t coming out as much while another one was growing. You’re kind of having that right now. It’s hard to get the older people to come out, and the younger people is slowly populating the music scene.

Jimmie Vaughan and W.C. Clark at Antone’s (photo Gary Miller)

Some of the young people call me the old-school, “Hey Old-School!” Well, Bobby Jordan said: “If you don’t learn the skills of the day, you can’t do the work of tomorrow”. Well, it’s the same thing about the music. If you don’t learn what is going behind, all you’re doing is starting off right in the middle and going forward. And then you don’t know what’s happening behind. Well, it’s a lot of musicians caught up in that. But then there’s a lot of musicians are just playing musical scholars, and they will be interested in knowing what was going on behind, coming up from the very beginning as much as possible.

That’s the way the music scene was back into the seventies and in the eighties when everybody was getting this old, old, old blues records, and records of guys playing the blues in the penitentiary and stuff like that. They were studying that stuff. They will really study it.

Style

“When you go ahead and listen to the blues, open your mind up, and enjoy it just for what it is, when you leave you kind of got a clean feeling in the soul. It’s not sadness, it’s the blues.”

Some people have described your music as a blending of traditional blues and R&B/Soul with the kind of Stax-like horn arrangements. How do you feel about that?

Well that’s true. As I explained, I was interested in any category of music if it was good. But see, in my experience I had to learn those categories before I could be satisfied myself and learn how to not play one category on top of the other category because of the rudiments and the pattern of the category of music I was playing. I played in the club Charlie’s Playhouse and the lady will get all top forty songs. I played that for quite a few years with Blues Boy Hubbard and the Jets. We had to play on the top forty songs; The Beatles, Otis Redding, B.B. King, all the blues, Bobby Bland, very little Chuck Berry. So we would be soul, blues, and swing. We used to call it progressive blues which is more jazz than it is blues. By doing all the different things and playing jazz on bass with James Polk, I had to learn all these different categories of music and do the best I can with it. So that’s still in me now.

I got 6 CDs up there [WC Clark points at his biographic board, which hangs in the Victory Grill’s wall]. My first album, WC Clark Blues Revue, is “Something for Somebody” (Drippin’ Springs Records, 1986). That was the first one but all 6 of those CD’s I won WC Handy awards either “Best Blues”, “Best Blues and Soul”… One of them got “Best Blues and Soul” and “Blues song of the year”. And another one won the WC Hand for… how did they phrase it? “More needed recognition”, or something like that. But they have all have won awards and I won all kind of awards in Austin, over, over and over. That’s who I am.

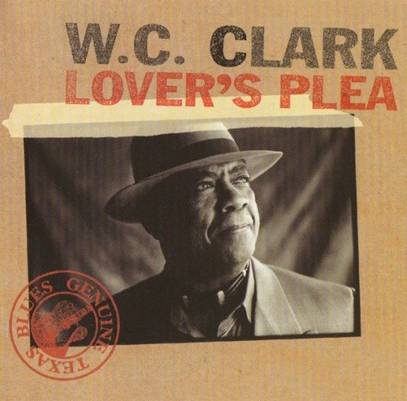

Lover’s Plea (Black Top Records, 1998)

Traditionally, blues is though as a sad music genre. But I think many of your songs have always a positive way out. Perhaps I listened a lot to Lover’s Plea…

See, the blues is in it. Just about everything I play got blues in it but I am not just a basically blues musician. I can do blues but I can do other things too and other styles of music too. I want to express all of it because when I perform I want the people to dance. I run a test on the audience with a few songs to see where they’re at. And once I find out where the audience is, I’m gonna feed them the style of music they need in order to dance. So, if the club owner sees the people dancing, well he gonna sell liquor and everything will be going on good.

Well, that’s the advantage of me knowing all these categories; I can use them. See, if I play to an older crowd like a wedding or something, I’ll do a lot of ballads because old people don’t wanna dance swing first. I do ballads and soft stuff. If you watch them on the floor, don’t let them dance too long. I do all that. And I do get a lot of weddings and business conferences and stuff like that. I do a lot of stuff for the city, for the mayor and the governor. New building or something like that, I play for it and things like that.

What do you feel about the so-called Rock ‘n’ roll explosion? Was it a new music? What was its relation with race music?

There was some soul music that was intended to be protest music, and race was involved a lot of times. But soul music has got a broad range. Soul music is more like gospel music than blues is. And the feeling… Blues words are sad but if it’s played right, and the singer is living it right, the listeners won’t be sad because the blues will tell them something that they won’t admit to themselves.

Soul music is more like “thank you” and blues is more like “this is what happened” or “this is what’s happening”. There is a little protest in both blues and soul music but blues was never really a segregated music. It wasn’t intended to be that way. Blues has always been open and integrated for the whole world to listen to it. In fact, there was an Italian gentleman named Alan Lomax. He made his thing to go down to the penitentiary and record those blues and registered them in the Library of Congress. That was a great idea. He was one of the people who helped bring the blues out of the cotton fields and the penitentiary, and make it broad for the whole world to listen to.

W.C. Clark Blues Revue (Tom Robinson on sax, Pete McClaren on bass, and Dexter Walker on drums) playing at the Central Market (photo WC Clark)

The same music can make one man feel bad and another man feel good, at the same time. That just lets you know that the results of that night is the music bringing out of that person what he already feels. Because when you listen to the blues, you don’t want to admit it but when someone goes: [singing] “It’s all over baby, I know I’m the one who did you wrong”, you might not wanna admit that to her, but when you hear that on a record you go: “Yeah. Damm, I did it!” See what I’m saying? That’s the way I was feeling in the first place. The person that can admit it from the blues, it won’t be sad to them.

But if the person is going: [Grumbling] “Yeah, but it was my fault”, they still haven’t completed anything in the feeling. So they’re gonna be sad: “Oh, that’s too sad. I don’t wanna hear that, it’s sad”. And they don’t realize it’s them, not the music. When you go ahead and listen to the blues, open your mind up, and enjoy it just for what it is, when you leave you kind of got a clean feeling in the soul. It’s not sadness, it’s the blues.

What about those 1940s musicians that were considered rhythm and blues and they would be in a separate chart to the pop chart? People like Big Joe Turner, Louis Jordan…

That’s what we we’re calling progressive blues back then, which was blues with jazz overtones and stuff like that, and swing big band sound. Rock ‘n’ roll came out of all of that. You got your negative and you got your positive. Well, rock ‘n’ roll came along and started drawing more of a negative feeling than the blues had. It was more attractive because it had a lot of negative energy.

It made you wanna do things like jump off the stage and expect somebody to catch you. You’ll never find a blues player doing things like that because there’s a different kind of energy he’s got. He’s got a positive energy that’s pleasing to the ear. Rock ‘n’ roll would be so loud until you don’t have to listen. Coming from the old school you had to listen to those old 2-track LP. You had to listen and then you’ll find out the more you listen, the more you hear. “I didn’t hear that in that last time”, but now people don’t listen because they don’t have to. So everything is so loud, it creates a kind of a negative energy. I play all of it. Music is what I do, and I got to make a living [giggles].

“Then all the children will sing: ‘I got the breakfast blues’”

Do you feel that music is appreciated differently in the United States and overseas?

Well, there’s a difference in the time. Today the music scene Italy, Germany, Turkey, Russia, and those places is more or less equivalent to the way it was in the United States in the ‘70s. Over there, they listen to old Frank Sinatra stuff, and they listen to the old blues, Muddy Waters… Well, that’s the way it was right here in the ‘70s. Kind of was like that. I can go to different countries and see that same scene today, just like that, like it was then. You can experience the same feeling because the same music is going on.

Major Burke was talking to some people in Japan one time and they wanted him to record a blues song, set it to them, and they were gonna take the voices out, use the music, and sing it in Japanese. That type of interest about music in the ‘70s was real strong like that in Austin, Texas.

W.C. Clark playing acoustic guitar (photo Diana Hendricks)

If you weren’t doing music for living, what would you do?

Well, I started off as a mechanic. My dad was a mechanic, he owned a garage. I worked for a few years raising my children, and I finally came to the position where I had to make a decision. Either I was gonna play music or work. I was struggling trying to do both and I wasn’t getting there. So I made a decision, to play music. Now I haven’t had a job in probably about forty years and I lived off music only and did fine. Still doing great.

Tell me about your future plans. Do you have any goals?

Well, I wanna make children video software; Blues video software for children. Clean blues, exciting blues, make myself a character… I am studying animation. I’m at the level now where I can draw the character, put all the bones together, and make it walk, but that’s just a small distance. Once I get the character and all that settled, then I got to synchronize the music and the video.

For instance, I’m just giving you a little short version of this. The name of the song is the breakfast blues: [singing] “I woke up this morning for breakfast treat?” and there’s a little boy getting up out of bed, and he’s walking half asleep. There’s a little bubble up there, only he can be this character. He goes to the table, looks down, and says “I don’t want that”: “And all my mama gave me was some shredded meat” You know what I mean? Then somebody whispers in the ear: “I told my little brother that I need… How much? Go out to the store and get some catholic brunch”. Then all the children will sing: “I got the breakfast blues”.

At the end of the video, after all those blues scenes, I come to play for the children for real; I’m a real person there. I have my whole line up there and I’m playing the breakfast blues too. Those kind of things.

You want people to see the blues, and get new generations into it…

Yeah. It’s gonna be clean so there won’t be any bad words that kids can listen to. That’s what I’m working on right now. That’s what I wanna do. I already got two websites. That’s not stopping me from playing. I’m still gonna be playing. But I wanna do that because I need to stay busy.

How do you study animation?

I study on my computer. I bought software and I’m teaching myself.

Same you did with music?

Same I did with music. Same I did with all the audio. Like I said, I can play all the parts and make my own CD, and label it, and it’s finished; master. Well I taught myself how to do that too. I got my wife to thank for. She’s a school teacher, very intelligent in technology. She keeps me on my toes.

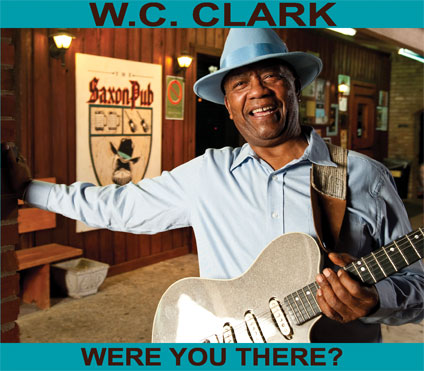

W. C. Clark

Name: W. C. Clark

Date of Birth: November 16, 1939

Location of Birth: Austin, Texas

Profession: Bandleader, songwriter, musician

Instrument: Guitar

Vocalist: Yes

Bands: T.D. Bell and the Cadillacs, Southern Feeling (with Angela Strehli), Triple Threat Revue (with Stevie Ray Vaughn)

Collaborators: T. D. Bell, Erbie Bowser, Angela Strehli, Steve Ray Vaughn

Discography: Something for Everybody (1986), Texas Soul (1994), Heart of Hold (1996), Lover's Plea (1998)

Influences:T.D. Bell

Styles: Blues, R&B

Venues: Various; Victory Grill, Charlie's Playhouse, (Charlie) Gilden's Chicken Shack

Like Blues Boy Hubbard, Clark has been a mainstay in the Austin blues scene since the Victory Grill years. Unlike Hubbard, Clark has a broad West Side audience -- perhaps the only Black East Side veteran to have continued career success.

Clarks career illustrates the fundamental premise of the project -- that present-day Austin blues/R&B can be directly linked to the times and figures of the East 11th/12th Street heyday. Clark came into the local scene through familial ties, and worked with music legends of the Austin 1950s, such as T. D. Bell and Erbie Bowser, and now maintains the traditions he learned as an apprentice in those East Side barrooms.

Today, however, that same music is being played for very different audiences in very different venues. Clark is very much aware of how the East Side has lost its practical connection to the local blues scene, and his insight and personal history are important to the Blues Family Tree. Clark's membership (often as leader and mentor) in bands with younger white blues players also provides a striking illustration of the evolution of Austin's modern day blues scene. The next generation of Austin blues players, the current students of the African American blues tradition, are with few exceptions Anglo and male.

Social Media